Ansible Variable

Ansible, the powerful automation tool, offers a wide range of features to simplify IT infrastructure management. One such feature is the use of variables, which allow for dynamic and flexible configurations. In this blog post, we will dive deep into the world of Ansible variables and explore how they can enhance your automation workflows.

Variables in Ansible serve as placeholders for dynamic values that can be used across playbooks, roles, and templates. They provide a way to customize and parameterize your automation tasks. Whether it's defining host-specific properties or storing sensitive data securely, Ansible variables offer great versatility.

Ansible supports various types of variables, including global, playbook-level, and role-specific variables. Understanding the scope of variables is crucial for managing their values effectively. We will explore how to define and access variables within different contexts and discuss best practices for maintaining variable consistency.

In complex Ansible projects, it's common to have multiple variables defined at different levels. This section will shed light on the order of precedence for variables and how overrides work. We will learn how to prioritize variable values and handle conflicts gracefully, ensuring that the desired configuration is achieved.

Dynamic variables take Ansible's flexibility to the next level. These variables are derived from system facts, registered task results, or the output of other tasks. We will discover how to leverage dynamic variables to create more intelligent and adaptive automation playbooks.

Securing sensitive information is paramount in any automation solution. Ansible provides a secure way to encrypt variables using the Ansible Vault feature. In this section, we will explore how to encrypt sensitive data, such as passwords or API keys, and seamlessly integrate them into your automation workflows.

Ansible variables are a fundamental aspect of building robust and adaptable automation solutions. From customizing configurations to handling sensitive data, variables empower you to achieve greater control and flexibility. By mastering the art of using variables effectively, you can unlock the full potential of Ansible and streamline your IT operations.Matt Conran

Highlights: Ansible Variable

Managing & Configuring Systems

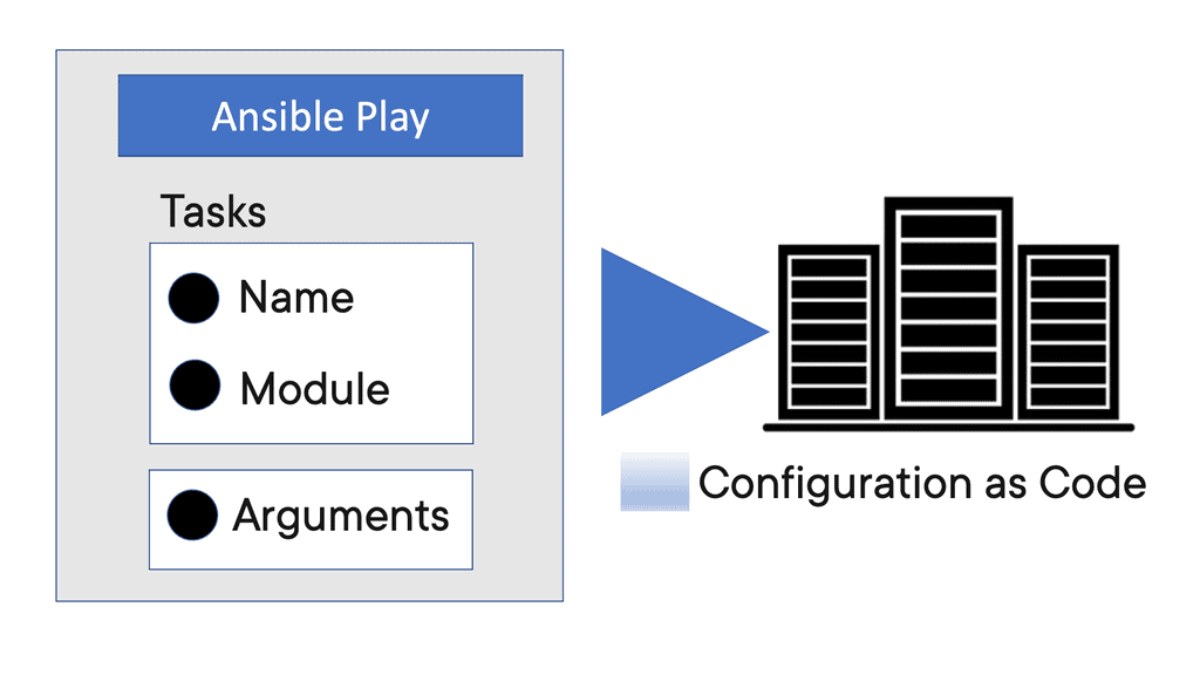

In the world of automation, Ansible has emerged as a popular choice for managing and configuring systems. One of the key features that sets Ansible apart is its ability to work with variables. Variables in Ansible enable users to define and store values that can be used throughout the playbook, making it a powerful tool for automation.

Variables in Ansible can be defined in various ways. They can be set globally, at the playbook level, or even at the task level. This flexibility allows users to customize their automation process based on their needs.

Variables: Values Specific to Different Environments

One everyday use case for variables is storing configuration values specific to different environments. For example, you have a playbook that deploys a web application. Using variables, you can define the database connection string, the server IP address, and other environment-specific values separately for development, staging, and production environments. This makes reusing the same playbook easy across different environments without modifying the code.

Variables: Dynamically Created

Another powerful feature of variables in Ansible is their ability to be dynamically generated. You can use calculated or fetched variables instead of hardcoding values at runtime. For example, the “lookup” plugin can read values from external sources like files or databases and assign them to variables. This makes your automation process more dynamic and adaptable.

**The Process of Decoupling**

For your automation journey, you want to be as flexible as possible. For this reason, within the Ansible architecture, we have a process known as decoupling. Here, we are separating site-specific code from static code. Anything specific to a server or managed device, such as an IP address, can be replaced with Ansible variables. As a best practice, always aim to have flexible playbooks, and if you want to share with someone else, all you need to change is the variables.

A) Variable Locations

As you know, variables are defined in several places. Each place you define the variables, such as the inventory with the ansible inventory variable or play header, will have an order of precedence. The most common place is for the Ansible set variables task. When you have Ansible set variables in the task, Ansible also allows setting variables directly in a task using the set_fact module. We will look at Ansible set variables in a task in a moment.

So, for an Ansible architecture with more extensive playbooks, remember the best place to hold your variables and not keep your playbooks site-specific. With Ansible, you can execute tasks and playbooks on multiple systems with a single command.

B) Ansible Tower

With Ansible Tower, you can have very complex automation requirements with the push of a button. Every site will have variations, and Ansible uses variables to manage system differences. To represent the variations among those systems, you can create variables with standard YAML syntax, including lists and dictionaries.

Before you proceed, you may find the following posts helpful:

Ansible Variable

Defining Ansible Variables

Ansible is open-source automation and orchestration software that can automate most of your operations with IT infrastructure components, including servers, storage, networks, and application platforms. It is one of the most popular automation tools in the IT world and has strong community support, with more than 5,000 contributors worldwide. With Ansible, we use variables.

Ansible uses variables to manage differences between systems. With Ansible, you can execute tasks and playbooks on multiple systems with a single command. To represent the variations among those systems, you can create variables with standard YAML syntax, including lists and dictionaries.

Ansible set variables in the task

Ansible is not a full-fledged programming language. However, it does have several programming language components. One of the most significant of these is variable substitution. The most straightforward way to define variables is to put a vars section in your playbook with the names and values of variables.

Here, we can have Ansible set variables in the task. The following will list the various ways you can set variables in Ansible. Keep in mind that we have an order of preference when doing so.

You can define your variables in several places: your playbooks, inventory, reusable files or roles, or at the command line. During a playbook run, you can create variables by registering a task’s return value or value as a new variable.

When defining variables in multiple places, they have variable precedence. After creating variables, you can use them in module arguments, such as conditional “when” clauses, templates, and loops. All of these are potent constructs to have in your automation toolbox.

Define variables: Vars: Section

If you are starting your automation journey, the simplest way to define variables is to put a vars section in your playbook with the names and values of variables. This allows you to define several configuration-related variables. So, to define variables in plays, include a vars: section in the header of the play where the variables are needed.

Variables defined in plays are only valid within that specific play and don’t have playbook scope. So, if you need a variable in a different play, you must define it again. This may be inconvenient and difficult to manage across extensive playbooks with multiple teams working on playbook development.

Define variables: Set_fact Module.

We also have the set_fact module. This module is used anywhere in a play to set variables. Any variable set this way applies as a fact to the host in which it is set. The set_fact relates the variable to the host used in the play.

Here, you can dynamically set variables based on the result of any task in the playbook. So, set_fact dynamically defines variables. Keep in mind that setting variables this way will have a playbook scope.

Define variables: Vars_files

You can also put variables into one or more files using the section called vars_files. This lets you put variables in a file instead of directly in the playbook. What I like most about setting variables this way is that it allows you to separate variables that contain sensitive information. When you define variables in reusable variable files, the sensitive variables are separated from playbooks.

This separation enables you to store your playbooks in, for example, source control software and even share them without the risk of exposing passwords or other sensitive personal data. So, when you put variables in files, they are referenced in the playbook using vars_files.

Use var_files to specify a list of files that include variables you want to include. This is convenient when you want to manage the variables independently of the place using them and is helpful for security purposes.

Define variables: Vars_Promt

So, here, we can use vars_promt in the play header to prompt users for a variable value. This has a playbook scope. By default, the variable is flagged as private, so the user does not see anything while entering it. We can if we have set private to no here.

Define variables: Defining variables at runtime

When you run your playbook, you can define variables by passing them at the command line using the—- extra-vars (or—e) argument.

Define variables: Task Variables

Task variables are made from data discovered while executing tasks or in the fact-gathering phase of a play. These variables are host-specific and are added to the host’s host vars. Variables of this type can be discovered via gather_facts and fact modules, populated from task return data via the register task key, or defined directly by a task using the set_fact or add_host modules.

**Facts / Variables**

Ansible Fact: System Variables

Ansible facts are a type of variable. You don’t define Ansible facts; they are discovered. Facts are system variables that contain information about the managed system. Each playbook starts with an implicit task to gather facts. This can also be disabled in the playhead. Gathering facts takes time, so if you are not going to use it, we can disable it.

We can also gather facts manually by using the setup modules. All of the facts are stored in one big variable called ansible_facts. However, within the variable, we have the second-tier variables. All of the facts are categorized into different variables. These facts are variables, and you can use the facts in conditionals and when statements.

Speeding up Fact Gathering

Fact collection can be slow as you may work against many hosts you can use and set up a fact cache. If fact-caching is enabled, Ansible will store facts in a cache for the first time; it connects to the host. This is added to your Ansible.cfg with the “fact_caching_timeout” value. So if your playbook does not reference any ansible facts, you can turn off fact-gathering for that play. Here we use the “gather_facts” clause in the play and the Ansible.cfg.

**Ansible Inventory Variable**

Ansible Variables are a key component of Automation. They allow for dynamic play content and reusable plays across different sets of inventory. Variable data, such as specific details on how to connect to a particular host in your inventory, can be included along with an inventory in various ways.

While Ansible can discover data about a system during the setup phase, not all data can be found. We can define data with the inventory that will expand what Ansible has been to discover.

Ansible variables: The Ansible inventory variables

- Host and group variables

In inventory, you can store variable values related to a specific host or group. This allows you to add variables directly to the hosts and groups in your main inventory file. Adding more managed nodes to your Ansible inventory will likely allow you to store variables in separate host and group variable files.

- [host_var and group_var]

Ansible looks for host variable files in a directory called host_vars and group variable files in a directory called group_vars. Remember that Ansible expects these directories to be in either the directory that contains your playbooks or the directory adjacent to your inventory file. You can break things out even further if you want to go further. Ansible lets us define, for example, group_vars/production as a directory instead of a file.

Behavior inventory variables

Behavioral inventory parameters allow you to describe your machines with additional parameters in your inventory file. Such as the ansible_connection parameter may be helpful. By default, Ansible supports multiple means of transport, which Ansible uses to connect to the managed host. Here is a list of some expected behavior inventory variables and the behaviors they intend to modify:

- ansible_host: This is the DNS name or the Docker container name that Ansible will initiate a connection to.

- ansible_port: This specifies the port number that Ansible will use to connect to the inventory host if it is not the default value 22.

- ansible_user: This specifies the username Ansible will use to communicate with the inventory host, regardless of the connection type.

**A key point: Ansible inventory scalability**

If you don’t have many hosts, you can use the inventory to store host and group variables. However, as your environment grows, managing variables in the inventory will become more challenging. In this case, you need to find a more scalable approach to keeping track of your host and group variables.

Even though Ansible variables can hold Booleans, strings, lists, and dictionaries, you can specify only Booleans and strings in an inventory file. Therefore, we have a more scalable approach to keeping track of host and group variables: you can create a separate variable file for each host and group. Ansible expects these variable files to be in YAML format, which allows you to break the inventory into multiple files.

Highlighting Ansible conditionals

– In a playbook, you may want to execute different tasks depending on the value of a fact, a variable, or the result of a previous task. You may wish to the value of some variables to depend on the value of other variables. You can do all of these things with conditionals. Ansible uses Jinja2 tests and filters in conditionals. Basic conditionals are used with the when clause.

– The most straightforward conditional statement applies to a single task. Create the Task, then add a when statement that applies a test. When running the task or playbook, Ansible evaluates the test for all hosts. For example, if you are installing MySQL on multiple machines, some of which have SELinux enabled, you might have a task to configure SELinux to allow MySQL to run.

– You would only want that Task to run on machines with SELinux enabled. Sometimes, you want to execute or skip a task based on facts. With conditionals based on facts, you can install a specific package only when the operating system is a particular version. You can skip configuring a firewall on hosts with internal IP addresses. You can perform cleanup tasks only when a filesystem is getting full.

**Ansible conditionals and When Clause**

You can also create conditionals based on variables defined in the playbooks or inventory. So, we have playbook variables, registered variables, and facts that can all be used in conditions and ensure that tasks only run if specific conditions are true.

**Handlers and When Statement**

There are several ways Ansible can be configured for conditional task execution. We have, for example, Handlers for conditional task execution. It is used when a task has changed something. Then we have a very powerful When statement. The When statement allows you to run tasks when specific conditions are true. You can also use the Register in combination with When statements.

**Using Handlers for conditional task execution**

A handler is a task only executed when triggered by a task that has changed something. Handler is executed after all tasks in a play, so you need to organize the contents of your playbook accordingly. If any task fails after the task is called the handler, the handlers are not executed. We can use the “force-handler: to change this.

Keep in mind that handlers are operational when something has changed. We have a force handler that allows you to force the handler to be started even if subsequent tasks are failing. Simply put, a handler is a particular type of Task that is called only if something changes.

**Handlers in Pre and Post tasks**

Each task section in a playbook is handled separately; any handler notified in pre_tasks, tasks, or post_tasks is executed at the end of each section. As a result, it is possible to execute one handler several times in one play.

- Using Blocks

Blocks create logical groups of tasks. Blocks also offer ways to handle task errors, similar to exception handling in many programming languages. Blocks can also be used in error conditional handling. So you have to use a block to define the main Task to run and then rescue to define tasks that run if tasks defined in the block fail. You can use “Always to Define” tasks that will run regardless of the success or failure of the Block and Rescue.

- Ansible loops

What happens, however, if you have a single task but need to run it against a list of data, for example, creating several user accounts, directories, or something more complex? Like any programming language, Ansible loops provide an easier way of executing repetitive tasks using fewer lines of code in a playbook.

Examples of commonly used loops include changing ownership of several files and directories with the file module, creating multiple users with the user module, and repeating a polling step until a particular result is reached.

**A final point: Managing failures with the Fail Module**

Ansible looks at a task’s exit status to determine whether it has failed. When any task fails, Ansible aborts the rest of the playbook on that host and continues with the next host. We can change this with a few solutions. For example, we can use ignore_errors in a task to ignore failure—force_handlers to force a handler that has been triggered to run even if another task fails.

But remember, there needs to be a change. We can also use these Failed_When, which allows you to specify what to look for in command output to recognize a failure. You may have a playbook used to clean up resources, and you want the playbook to ignore every error, keep going on till the end, and then fail if there are errors. In this case, when using the fail module, the failing Task must have Ignore Errors set to yes.

Summary: Highlights: Ansible Variable

Ansible, a popular open-source automation tool, provides many features to streamline IT operations. One such powerful feature is the use of variables. In this blog post, we delved into the world of Ansible variables, exploring their importance, different types, best practices, and practical examples.

Understanding Ansible Variables

Variables in Ansible serve as placeholders for dynamic values that can be used across playbooks and roles. They enable flexibility and reusability, making your automation workflows more efficient. This section covered the basics of Ansible variables, including variable declaration, scoping, and precedence.

Types of Ansible Variables

Ansible offers various types of variables to cater to different needs. Each type serves a specific purpose, From global to environment variables, extra variables, and facts. We explored these different types in detail, highlighting their use cases and how they can enhance your Ansible automation.

Best Practices for Working with Variables

To ensure smooth and maintainable Ansible projects, following best practices when working with variables is essential. This section provided valuable insights into structuring variable files, naming conventions, documentation, and organizing your variables for better maintainability and collaboration within your team.

Practical Examples

Putting theory into practice is the best way to solidify your understanding. This section will walk through real-world examples where Ansible variables play a crucial role. From dynamic inventory management to conditional statements and template rendering, you will gain hands-on experience leveraging variables to achieve desired automation outcomes.

Advanced Techniques and Tips

Once you fully grasp the fundamentals, it’s time to level up your Ansible variable skills. This section will dive into advanced techniques and tips, including variable manipulation, using Jinja2 filters, encrypted variables, and integrating Ansible with external data sources. Unlock the full potential of Ansible variables and take your automation to the next level.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, Ansible variables are fundamental to creating robust and flexible automation workflows. By understanding their significance, exploring different types, and adopting best practices, you can harness their power to simplify complex deployments, increase reusability, and maintain cleaner code. Embrace the world of Ansible variables and unlock unparalleled automation capabilities.

- Fortinet’s new FortiOS 7.4 enhances SASE - April 5, 2023

- Comcast SD-WAN Expansion to SMBs - April 4, 2023

- Cisco CloudLock - April 4, 2023